In Greek mythology, Chiron set himself apart from the other centaurs. While most chased reckless appetites, he devoted his life to teaching, healing, and guiding others into their strength. He taught some of the most renowned figures in myth, yet his legacy lived in the inner resources he helped them build. His story reminds us that learning how to be a better parent begins with nurturing the qualities that will serve a child long after we are gone.

Parenting is much the same. It asks you to prepare your children for a life you cannot fully imagine. You equip them with resilience, judgment, and self-trust, knowing they will one day face decisions without you. This preparation is not done in a single moment, but in countless, ordinary interactions, the ones you might not even remember years later, but that will carry like stones in the foundation of their life.

The role shifts constantly. At times, you hold close, steadying them when the world feels too big. At other times, you step back so they can test their footing. This rhythm between presence and distance cannot be scripted. It requires sensitivity, patience, and the willingness to be wrong sometimes, and to adjust. The years when you can directly shape their daily world are brief, but the imprint you leave will outlast your presence.

In the blog that follows, we will explore how parents can navigate this shifting role with wisdom, drawing on decades of research in developmental psychology and family systems theory. We will look at the early formation of secure attachment (Bowlby, Ainsworth), the cultivation of competence and autonomy (Deci & Ryan), the balance of warmth and structure in discipline (Baumrind), and the modelling of values through lived example (Bandura, Frankl). These concepts will not appear as distant academic abstractions, but as practical, human truths: the kind Chiron himself might have recognized, woven into the everyday work of raising a child to meet a world that will one day be entirely their own.

The Fleeting Early Years: Building a Safe Place to Return To

In the earliest stage of life, safety is not an idea; it is a feeling in the body. A baby doesn’t understand trust in words, but they learn it through repetition: when they cry, someone comes; when they are frightened, they are soothed; when they reach out, they are met. Bowlby’s attachment theory, supported by decades of research, calls this the “secure base”, the internalized sense that the world is not random and that they are not alone in it.

The mistake some parents make is assuming this base will form automatically. It doesn’t. It grows from a thousand small moments: the glance you return across the room, the way you kneel when they approach, the tone of your voice when you respond. Out of all of this, what stands out is that these moments are not about perfection, but about consistency. Children do not need an unbroken record of attunement. They need to know you will return and try again when you miss the mark.

And the urgency here is real. These years compress quickly. In the thick of them, the days feel long, but one day you will look back and realize the stage when you were their whole world has already passed. When you understand this while it’s happening, you start to treat these interactions differently. You pause to meet their gaze. You return the call for help instead of delaying it. Each of these acts becomes part of the invisible scaffolding they will one day climb to face a much larger world.

How to Be a Better Parent: Growing Competence Without Overindulgence

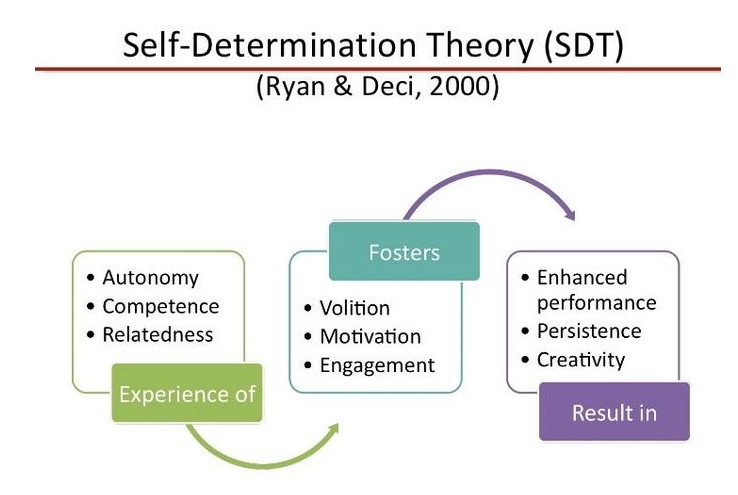

It is tempting to protect children from struggle. Parents sometimes think that doing for them is a sign of love, when in fact it can quietly erode their sense of capability. Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory places competence alongside autonomy and relatedness as one of the three basic psychological needs. Without it, confidence has no foundation; it becomes dependent on outside praise rather than anchored in lived experience.

The wisdom here is in tolerating the discomfort of watching them wrestle with a task. This is the part that feels slow and messy: tying shoes with clumsy fingers, reading haltingly through a page, cleaning up a spill they caused. When you step in too quickly, you remove not just the obstacle but also the chance to see themselves succeed. As such, it is paramount to let one’s child feel the full arc of an effort, so that they need to know not just the outcome, but what it feels like to work toward it.

Giving children responsibilities within the family reinforces this. When they set the table, water plants, or pack their bag, they aren’t just learning a task; they are learning that they have a place in the shared work of life. This sense of being useful has long-term effects. Studies show that children who feel their contributions matter are more likely to persist in challenges, recover from setbacks, and approach new situations with initiative.

Sharing Roles of Nurture and Challenge

In many families, one parent becomes the comforter and the other the challenger. This pattern might seem natural, but over time it limits the child’s view of each parent and, by extension, of relationships in general. Research on co-parenting points to the benefits of fluidity: when both parents can offer warmth and also set expectations, children develop a more balanced understanding of love and support.

Switching roles is not about abandoning your natural style, but expanding it. A parent who usually provides comfort can also be the one who encourages a leap forward. The parent who often sets challenges can also offer rest and reassurance. When a child sees that either parent can meet their needs for safety and growth, they learn that care is not bound to one personality or one role.

Furthermore, there should be an emphasis on “wholeness in parenting,” so that a child benefits most when they experience the full spectrum of care from each parent. This doesn’t just prepare them for independence. It teaches them that the same person who urges them to try again will also stand beside them when they stumble. That kind of trust is difficult to break, because it is built on a broad, lived-through experience of a relationship.

How to Be a Better Parent: Discipline as Teaching

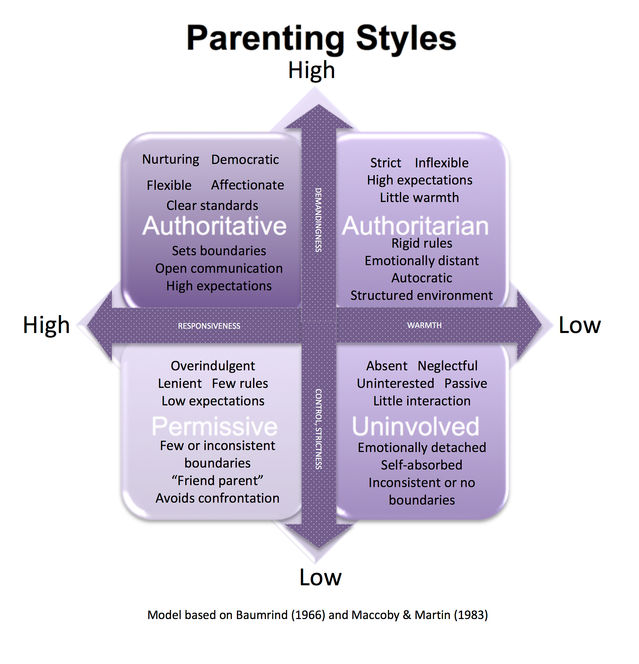

The word “discipline” often carries the wrong associations: punishment, control, and fear. But its root is the same as “disciple,” meaning to teach or guide. Diana Baumrind’s research on parenting styles, later refined by Maccoby and Martin, organizes parenting into four main approaches based on two dimensions: responsiveness (warmth) and demandingness (structure).

In the image, these dimensions form a grid. High warmth and high structure create the authoritative style: nurturing, flexible, and affectionate, yet clear in expectations and boundaries. Authoritative parents combine guidance with support, encouraging open communication while holding consistent standards. This balance fosters self-reliance, emotional regulation, and strong social skills.

In contrast, authoritarian parents show high structure but low warmth. Their rigid rules and emotional distance can lead to compliance in the short term but often at the cost of self-esteem and autonomy. Permissive parents offer warmth but low structure, leading to inconsistency and difficulties with self-control. Finally, uninvolved parents score low on both warmth and structure, which research links to the poorest developmental outcomes.

Decades of psychological literature confirm that authoritative parenting best equips children for the challenges of adulthood. It reflects a philosophy of discipline as teaching rather than control: a way of preparing children for independence while keeping the bond of trust intact.

In practice, this means parents set boundaries that are clear and predictable, yet never arbitrary. They connect a bedtime rule to the reality that rest supports growth and learning. They link a rule about honesty to the trust that allows a family to work together. When a child breaks a rule, the parent shifts the focus from punishment to understanding. What happened? What can be done differently? The consequence becomes part of the learning, not separate from it.

As such, discipline should protect dignity. How to be a better parent is through correcting behaviour without shaming the child’s character. When discipline maintains respect, the child learns that mistakes are part of growth, not evidence of being unworthy. Over time, this fosters a mindset where rules are internalized, not just followed to avoid consequences.

The Slow Art of Stepping Back

One of the hardest skills in parenting is knowing when to step away. The instinct to protect is strong, and in many cases, it is the right response. But growth often happens in the space where a child must navigate a challenge without constant direction.

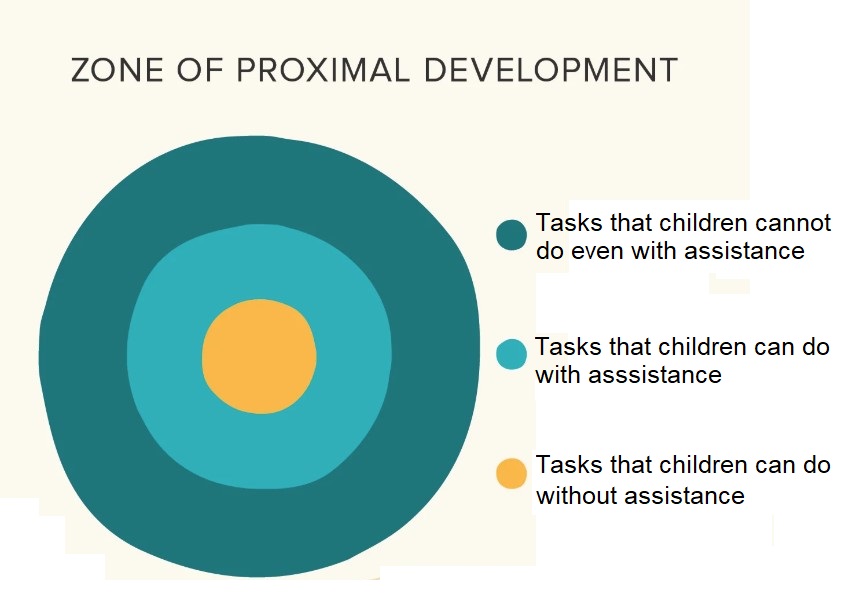

Lev Vygotsky’s concept of the “zone of proximal development” describes the sweet spot for learning: a task that is just beyond what the child can do alone, but achievable with minimal guidance. In practice, this means holding back just enough for them to struggle productively. Too much help can rob them of the learning. Too little can leave them discouraged or unsafe.

There is what one can call the “discomfort of silence,” where a parent’s role in those moments is often to endure their unease while the child figures it out. You may want to finish the puzzle piece for them, explain the answer, or rush in to correct the mistake. But if you can stay with your discomfort, you give them the gift of mastery. Each small success, tying the knot, getting the answer, fixing the error, becomes a reference point they carry into harder challenges later in life.

The art of how to be a better parent lies in calibration: we remain close enough to catch them if they fall in a way that could cause harm, yet far enough that the outcome belongs to them. Over the years, these choices create a bridge from dependence to independence, one that is strong because we allowed them to walk across it on their terms.

How to Be a Better Parent: Building Bonds Beyond Birth

The bond between parent and child is often assumed to be automatic, as if blood alone guarantees connection. But research on foster and adoptive families shows otherwise. Secure attachment is built through reliability, presence, and care over time, not simply through biology.

For step-parents, this truth can be both freeing and challenging. It means you are not locked out of a genuine bond simply because you arrived later. It also means there is no shortcut. Again, it relies on a slow accumulation of ordinary days, the school drop-offs, the shared meals, the listening without judgment. Each of these moments is a stitch in a fabric that may take years to complete.

Children in blended families often watch carefully before deciding to trust. They may test, withdraw, or compare you to the parent they already know. Patience here is not passive; it is active, steady, and attentive. Every time you show up when you say you will, respond without dismissing, or share in a small joy, you place another thread in that fabric. Over time, those threads become strong enough to hold the weight of a real connection.

Living the Example You Want Them to Follow

Children learn as much from what you do as from what you say, often more. Albert Bandura’s social learning theory confirms what parents have always suspected: children model their behaviour on the actions they observe, especially from those they are closest to.

The integrity between our words and actions matters deeply. A child who hears respect in our speech is more likely to offer it in their own. They are drawn toward curiosity when they see us approach the unfamiliar and stay with it. They learn humility when they watch us acknowledge mistakes without defensiveness.

What we can essentially learn from Bandura’s theory is that our children will remember what we lived more than what we lectured. Our habits, tone, and reactions are a living curriculum. Even the way we handle conflict with our partner or treat strangers leaves an imprint. Over time, these lived examples form the mental blueprint your child will draw on when deciding how to act in their own life.

Responsibility as a Source of Meaning

Parenting can be exhausting, unpredictable, and humbling. Yet for many, it also becomes the deepest source of meaning in life. Viktor Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor who founded logotherapy, a therapeutic approach centered on the idea that the primary drive in human beings is the search for meaning. He believed that even in the most difficult circumstances, people can find purpose by choosing their attitude and committing themselves to values, responsibilities, and relationships that transcend personal comfort. In parenting, this perspective reminds us that caring for a child is not only about meeting daily needs, but about stepping into a role that can define one’s life with depth, direction, and enduring significance. His work reminds us that meaning often arises when we take responsibility for someone or something beyond ourselves.

Caring for a child gives shape to your days in a way little else can. Even the most mundane routines, preparing meals, helping with homework, guiding them through emotional storms, are acts that tether you to a purpose larger than your immediate wants. Research on caregiving satisfaction finds that parents who embrace this responsibility fully often report greater life satisfaction, even in the face of fatigue or stress.

Thus, responsibility is the anchor you can hold when nothing else feels steady. In parenting, the anchor is not about control. It is about showing up again and again, even when the rewards are not immediate. This consistency becomes a form of love that the child may only understand fully when they are grown.

The Bow and the Release

Chiron’s life was defined by preparing others for a journey he could not take with them. The image of the bow and arrow fits parenting for this reason. You place the arrow on the string, you draw it back with care, and you aim toward a horizon you will never reach yourself. Then you release.

The release is the part most parents fear. It can feel like a loss, as if all the years of care are ending. But release is not the end of influence. It is the moment when all the shaping, teaching, and guiding you have done move into the world through another person’s life.

One final reflection: as parents, we are both the harbour and the sea. You give your child a place to anchor when they need safety, and you also give them the water they must learn to navigate. How to be a better parent requires the balance between those two roles, the holding and the letting go as the essence of the work.

If you are ready to explore your own journey as a parent, Luceris is here to walk alongside you. You can book a session or contact us today to begin.