Every human life depends on structures of order. From childhood onward, we develop systems of belief and behavior that allow us to navigate a complex world. These structures provide safety and predictability, and they help us make sense of our place in the wider environment. Yet what often goes unrecognized is that these very systems contain the seeds of their own collapse. Psychological structures, like political kingdoms, inevitably decay when they are not renewed. The patterns of thought and behavior that once offered stability gradually lose their flexibility. What begins as protection hardens into rigidity, and over time, the rigidity becomes a source of suffering, making renewal possible only by breaking old patterns in therapy.

Clinical psychology has long observed this process. Freud described it as repetition compulsion, the tendency to unconsciously reenact patterns from earlier life even when they no longer serve us. Jung saw it in the archetype of the “senile king,” the ruler who resists change and becomes blind to the forces of decay within his own kingdom. Contemporary cognitive and behavioral models describe the same process as the entrenchment of maladaptive schemas, core beliefs about the self and the world that shape perception and behavior, even when they perpetuate distress. In acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), the same phenomenon is called experiential avoidance: strategies that once reduced suffering end up amplifying it when they are applied indiscriminately and without adaptation.

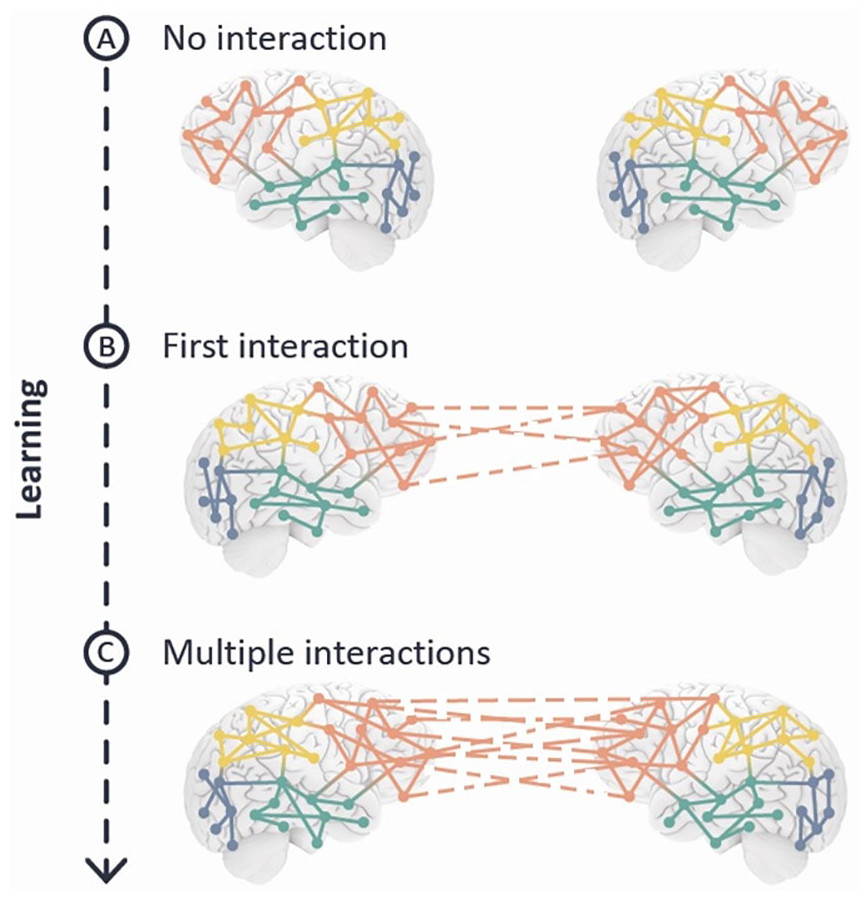

Additionally, neuroscience confirms this tendency toward rigidity. Neural networks strengthen with repeated use, a process often summarized as “neurons that fire together wire together.” This efficiency helps us respond quickly in familiar situations, but it comes at a cost. Without novelty and corrective feedback, the brain prunes away flexibility. Over time, networks designed to keep us safe become locked into loops that resist updating, even when the environment changes. Plasticity, which is most robust in youth, declines when it is not exercised. What once felt like stability becomes a trap maintained by the brain’s own architecture.

When clients arrive in therapy, it is often because their personal “kingdom” has reached a breaking point. Anxiety overwhelms the defences that once kept it at bay. Depression reveals the collapse of an identity built on outdated roles or unreachable standards. Relationships falter under the weight of rigid interaction patterns that no longer serve connection. In each case, it could be metaphorically said that the kingdom that once held order shows cracks, and the person can no longer sustain it. This collapse is painful, but it is also the moment where renewal becomes possible. Therapy provides the space to examine what has become tyrannical in the self, to tolerate the uncertainty of dismantling old patterns, and to build the flexibility required for growth. Renewal, therefore, becomes the necessary process by which both kingdoms and psyches continue to live: ultimately a process of breaking old patterns in therapy.

Breaking Old Patterns in Therapy: The King as Order, The Tyrant as Decay

Across cultures, the image of the king represents the archetype of order. The king brings stability by uniting the chaotic elements of the kingdom under a shared structure. In psychological terms, this reflects the way people create systems of meaning to regulate their emotions, organize their relationships, and manage their lives. Developmental psychology highlights how essential this process is. Children require consistent routines and boundaries to regulate affect and build trust in their caregivers. Erik Erikson framed this as the task of establishing basic trust and autonomy in early life. Piaget described the process in cognitive terms: children build schemas that help them predict how the world will respond. These schemas become the scaffolding of identity.

Yet the same structures that provide stability also carry the risk of stagnation. Archetypally, the king does not remain a benevolent ruler forever. With time, he can become rigid, blind to what is unfolding beyond the safety of the walls, and defensive when change threatens the old order. In myth, this is the tyrant king: Osiris unable to anticipate Set’s treachery, Mufasa blind to Scar’s resentment (The Lion King), or any ruler who mistakes yesterday’s strategies for tomorrow’s solutions. Jung saw this as the inevitable shadow of order, when the ruling principal resists renewal, it becomes oppressive.

Modern clinical theories describe the same dynamic. In cognitive-behavioural therapy, rigid schemas develop when beliefs that once offered safety, such as “I must achieve to be worthy” or “I must stay quiet to remain safe,” persist long after they are useful. Instead of adapting, the psyche clings to them, and they become tyrannical rules that generate distress. Emotion-focused therapy observes a similar process in relationships: couples caught in negative cycles enforce repetitive, rigid patterns of protection and attack. The “kingdom” of the relationship becomes dominated by a cycle that neither partner consciously chose but both feel powerless to escape, a cycle that can only be interrupted by breaking old patterns in therapy.

It can be seen in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning and regulation, that enforces order in the brain. It suppresses impulses from the limbic system and directs attention toward stability. But when over-relied upon, this system reduces flexibility. It defaults to efficiency rather than adaptation. The same circuits that once facilitated growth can trap a person in rigid habits of thought and behaviour. In extreme cases, this rigidity contributes to disorders characterized by compulsive repetition, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder or chronic anxiety, where the “order-keeping” circuits dominate at the expense of flexibility and renewal.

Therapy confronts this paradox directly. The client enters with a set of established rules, some explicit, others implicit, that form the governing principles of their life. These rules once had a function, but they are now failing. The therapeutic task is not to overthrow order entirely, but to help the client recognize where order has tipped into tyranny. In CBT, the focus is on examining beliefs for accuracy and flexibility, loosening their grip through evidence and behavioural experimentation. ACT frames the work differently, showing clients that clinging to control fuels suffering and that acceptance of uncertainty opens the possibility of renewal. Psychodynamic and Jungian approaches emphasize identifying where the archetypal king has grown blind, as well as where vitality is being lost to neglected forces in the unconscious.

Every kingdom requires order, but no order lasts forever. The challenge in therapy is to discern when the king has become a tyrant, when the very structures that once made life livable now restrict it, and to help the client move toward a new balance where order can once again serve growth rather than suppress it, where breaking old patterns in therapy is more likely to happen.

Entropy of the Self: How Psyches Become Tyrannical

In physics, entropy refers to the natural drift of systems toward disorder. Human psychology, though more complex, follows a similar principle. Unless renewed, the structures of the self gradually lose their vitality. What begins as adaptive regulation, coping strategies, identity roles, and relational patterns deteriorates into inflexibility and constraint. This is not a failure of character but an inevitable feature of living systems. Over time, what once supported survival can become the very mechanism that sustains suffering.

Again, Freud observed this in the phenomenon of repetition compulsion: the unconscious drive to reenact early relational patterns even when they lead to pain. A child who survived by pleasing an unavailable caregiver may, in adulthood, compulsively seek partners who cannot meet their needs. Jung described this same dynamic symbolically as the aging king who resists renewal. Rather than adjusting to the demands of the present, the psyche clings to the established order of the past, leaving the individual governed by a form of internal tyranny. Contemporary schema theory identifies this process with maladaptive schemas and modes. These enduring patterns, once functional, crystallize into distorted filters that shape perception, keeping the person trapped in cycles of distress; a prime example of the need for breaking old patterns in therapy.

It is worth repeating that the brain’s efficiency depends on reinforcement: neurons that fire together wire together. Each time a defensive behaviour is repeated, avoiding conflict, numbing with substances, or rehearsing self-criticism, the underlying network strengthens. Over time, these circuits dominate, making alternative responses less accessible. Hebbian learning, while efficient, promotes a kind of neural conservatism. Without disruption or new experience, the brain defaults to familiar responses, even when they are harmful. Chronic stress compounds this by over-activating the amygdala, narrowing attention to threat and further entrenching habitual defences. The hippocampus, essential for distinguishing past from present, becomes compromised under prolonged stress, which explains why old patterns can feel inescapably alive in the present moment.

Therapeutic models each grapple with this entropic drift of the psyche. ACT emphasizes how experiential avoidance strengthens over time. Each attempt to suppress unwanted feelings temporarily reduces distress, but also reinforces the belief that such feelings are intolerable, thereby amplifying their long-term impact. In CBT, the focus is on loosening the grip of entrenched schemas by testing them against lived experience, reintroducing flexibility where rigidity has taken hold. In psychodynamic therapy, the task is to bring unconscious repetitions into awareness so they can be worked through rather than acted out. Jungian analysis frames this as shadow integration: reclaiming the neglected and repressed aspects of the self before they consolidate into destructive patterns.

Ultimately, what unites these perspectives is the recognition that without deliberate engagement, the psyche will drift into rigidity. Left unchecked, beliefs, habits, and defensive strategies become the tyrannical forces of the self. Therapy provides the interruption, the opportunity to bring entropy into awareness and to deliberately engage the work of renewal. To do so requires not only insight but also the willingness to experience discomfort, for the dissolution of entrenched patterns is rarely gentle. Yet in this dissolution lies the possibility of reorganization and growth, the emergence of a self that is less constrained by yesterday’s defences and more capable of meeting the realities of today.

Floods, Fires, and Collapse: When Chaos Breaks Through

When order resists renewal long enough, collapse becomes unavoidable. Cultures have always recognized this truth and recorded it in their myths. Flood stories, found from Mesopotamia to the Hebrew Bible to indigenous traditions, portray the waters of chaos overwhelming civilizations that ignored the signs of decline. Fire serves as a similar symbol, purging, devastating, and yet clearing the ground for something new. These elemental images capture what occurs psychologically when a rigid system finally breaks. Chaos enters not as a polite visitor but as a force that overwhelms.

Clinically, collapse often presents as a crisis. The person who has long relied on control strategies, perfectionism, suppression, and avoidance reaches a threshold where these strategies can no longer contain experience. Panic attacks, depressive shutdowns, compulsive behaviour, or relational breakdowns are the floodwaters bursting through. They are not random malfunctions but the predictable outcome of systems stretched beyond their capacity to adapt. In trauma research, Bessel van der Kolk describes how unprocessed memories and emotions held in the body eventually erupt as flashbacks, somatic pain, or dysregulated affect. What has been refused expression forces its way into consciousness, much like water breaking through a dam that was never strong enough to hold it indefinitely.

As such, under sustained stress, the amygdala becomes hyperactive, heightening vigilance and amplifying emotional reactivity. The prefrontal cortex, which normally regulates emotion and maintains perspective, loses its regulatory grip when overwhelmed by stress hormones. This creates a feedback loop where intrusive thoughts and physiological arousal feed one another, leaving the person trapped in a state of chaos. Cortisol further impairs the hippocampus, weakening the ability to distinguish past threats from present reality. The individual is pulled under by an internal flood in which boundaries between then and now dissolve.

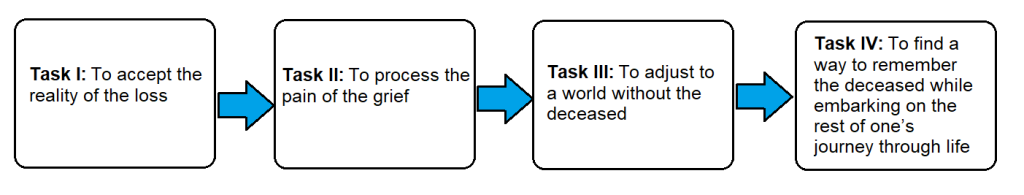

Therapeutic models recognize both the inevitability and the necessity of such collapses. In grief therapy, denial eventually yields to waves of intense emotion. Worden’s tasks of mourning emphasize that facing the pain of loss is unavoidable if healing is to occur.

In dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), therapists frame crises as opportunities to introduce and practice skills. Overwhelming affect creates the conditions where new regulation strategies become both necessary and possible. Exposure therapies follow the same principle: clients step directly into feared experiences, allow anxiety to crest and subside, and create the conditions for new learning. Chaos, though frightening, becomes the arena where renewal begins.

Floods and fires are not metaphors for destruction alone; they also point to purification and transformation. The collapse of the old order strips away what no longer serves, however painful the process may be. Therapy treats breakdown not as failure but as the very event that makes growth possible. The flood reveals cracks in the foundation, and the fire burns away the dead wood. Renewal begins only when collapse runs its course and makes room for building anew.

Breaking Old Patterns in Therapy: The Hero’s Descent into Renewal

If collapse is inevitable when old systems fail, the question then becomes how one responds to the aftermath. Myths across cultures tell us that renewal never occurs by avoiding the flood or skirting the fire. Renewal comes only when the hero descends into the very chaos that has been unleashed. Prometheus brings the gift of fire only by daring to trespass against divine order. Simba’s return to kingship does not happen in the safety of Pride Rock but in exile, after wandering in the wilderness of shame and denial. These narratives illustrate a psychological truth: growth requires descent, and that descent is often the beginning of breaking old patterns in therapy.

In developmental terms, Piaget described learning as a balance between assimilation, fitting new experiences into existing structures, and accommodation, reshaping structures to meet new experiences. Cognitive Processing Therapy adapts this framework to explain trauma recovery. When trauma occurs, individuals often over-assimilate by forcing the event into existing, often distorted, beliefs about themselves or the world (“It was my fault,” “I am never safe”). Others may over-accommodate, reshaping their entire worldview around the trauma in ways that become overly broad and rigid (“No one can be trusted,” “The world is entirely dangerous”). In either case, the psyche cannot integrate the experience flexibly, and suffering persists. The descent into chaos, then, is the process of moving beyond these extremes, letting go of outdated structures, tolerating the disorientation of accommodation, and gradually reorganizing beliefs in a way that restores coherence and allows for growth.

Thus, true change in the brain requires the destabilization of existing neural networks. When novelty and challenge are introduced, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) increases, supporting the growth of new connections. Neuroplasticity is not activated by comfort but by disruption. The very instability that feels overwhelming is what allows the brain to reorganize itself. In this sense, the descent into chaos is not simply symbolic; it is embodied in the neural process of unlearning and relearning.

Therapeutically, this descent takes many forms. In exposure therapy for anxiety, clients deliberately step into feared situations and allow the physiological storm to rise and fall without avoidance. ACT frames the process as willingness, turning toward pain, fear, or uncertainty rather than retreating into control. Psychodynamic work approaches descent through revisiting painful memories or uncovering hidden aspects of the self, a destabilizing process but one that is essential for integration. Even in grief therapy, progress depends on alternating between restoration and loss-oriented work, which means returning, again and again, to the painful reality of absence. These approaches all reflect the same underlying process: breaking old patterns in therapy.

The descent is not comfortable, nor is it quick. It often feels like regression, as if one has lost ground rather than gained it. Yet myths remind us that only by entering the underworld can the hero return with new wisdom. Therapy mirrors this ancient truth. To grow, one must tolerate the destabilization of descent, trust that chaos contains the seeds of renewal, and allow the psyche to reorganize in ways that cannot occur if one clings to safety. The task is not to avoid the underworld, but to walk through it with guidance and purpose.

The Shadow Brother: Why the Adversary Lives Within

In myth, the enemy is rarely a stranger. He is the brother, the one closest to the throne. Scar and Mufasa, Osiris and Set, Cain and Abel, each story shows that collapse comes not from outside invaders but from what has been neglected within. Psychologically, this figure represents the shadow: the parts of ourselves we refuse to acknowledge, whether aggression, envy, dependency, or vulnerability. What is denied does not disappear; it gathers strength in secret until it undermines the very order we are trying to preserve.

Clinically, shadow dynamics appear in many forms. Clients who pride themselves on patience may discover suppressed anger leaking into passive aggression. Those who live by self-reliance may find dependency emerging in destructive ways. Couples often project their shadows onto each other, blaming partners for qualities they cannot accept in themselves. Psychodynamic therapy names this the “return of the repressed,” while schema therapy frames it as modes erupting when left unintegrated. Jung’s insight remains clear: the adversary we most fear is the one we have not yet learned to face within ourselves.

Supporting why repression fuels intensity is that emotional suppression activates limbic regions like the amygdala, keeping threat systems online even when no immediate danger is present. The prefrontal cortex must then work harder to maintain control, which drains cognitive resources and heightens stress. Over time, the effort to contain the shadow creates more instability, not less.

So, therapy provides a deliberate space to meet the brother within. CBT approaches this by treating “forbidden” thoughts not as proof of pathology but as data to examine. ACT works with the shadow through defusion, helping clients observe thoughts and urges without being consumed by them. Jungian and parts-based models such as Internal Family Systems take an even more direct path, naming and dialoguing with the neglected figures of the psyche and guiding their eventual integration. Renewal requires this confrontation. Without it, the shadow continues its work from beneath the surface and waits for the moment when the kingdom grows most vulnerable, a struggle that clients confront by breaking old patterns in therapy.

Death and Rebirth: The Cycle of Growth

Every renewal requires a death. Myths express this with striking consistency: Osiris dismembered and restored, Inanna descending through the underworld before returning transformed, even religious figures like Christ crucified and resurrected. These images capture an essential psychological process. The old self must fall apart for something new to take its place. Growth is not simply additive; it is cyclical, involving endings, disorientation, and reorganization.

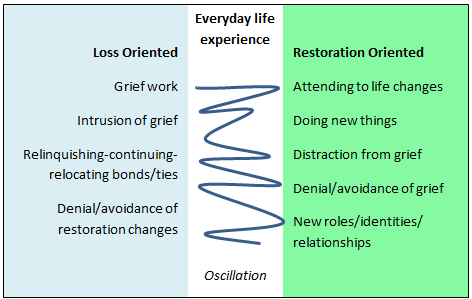

In psychological development, this cycle has been described in many ways. Erikson’s model of psychosocial stages highlights crises that demand the letting go of one identity before another can emerge. William Bridges’ work on transitions frames change as moving through endings, a neutral zone of uncertainty, and eventual new beginnings. In grief therapy, Worden’s tasks and the Dual Process Model both emphasize that the mourner must face the reality of loss while also oscillating between that pain and the adjustments of life without the loved one, rather than becoming stuck on one side. Renewal cannot bypass death; it depends on it.

During sleep, the brain prunes connections that are no longer needed and consolidates new learning. This nightly “mini-death” allows for adaptation by clearing space for reorganization. Without pruning, the system becomes overloaded. At a larger scale, the same principle applies to the psyche: clinging to outdated patterns prevents the brain and body from reorganizing around new possibilities.

Therapeutically, clients often resist this part of the process because it feels like failure or regression. Yet therapy reframes it as the necessary dismantling of what no longer works. In CBT, behavioural experiments are used to disconfirm old beliefs so that new ones can take root. ACT frames renewal through values-based living, which requires the willingness to release the false security of control. Psychodynamic and Jungian work highlight symbolic deaths, the collapse of illusions and the confrontation with shadow, as the turning point toward integration.

Death and rebirth are not abstractions but lived experiences: the end of a relationship, the collapse of an identity, the release of a defense that once felt essential. These moments hurt, but they also create the conditions for growth. Renewal begins only when the old order yields.

Therapy as the Work of Renewal

Therapy is where the cycle of collapse and renewal becomes deliberate rather than accidental. People often arrive when the old structures have already failed: anxiety breaking through defenses, depression signaling the collapse of meaning, relationships faltering under rigid patterns. What feels like personal failure is in fact the universal process of entropy catching up with the psyche. The therapeutic space offers containment for that collapse so it does not destroy but instead reorganizes.

Different models describe this in their own language. However, across therapeutic models, the therapist functions less as a problem-solver than as a guide, helping the client endure collapse long enough for renewal to begin. Neuroscience confirms the importance of this alliance: safety within the therapeutic relationship reduces amygdala activation and restores prefrontal regulation, making it possible for clients to confront what was previously unbearable.

Breaking Old Patterns in Therapy: Renewal as a Lifelong Task

Renewal is not a single event but a recurring demand. Each stage of life brings endings we must acknowledge and identities we must release so new ones can emerge. Myth reminds us that this cycle is eternal: the sun sets and rises, the seasons turn, the king grows old and another takes his place. The same is true within the psyche. Collapse is never comfortable, but it is also never meaningless. It clears the way for growth that could not occur otherwise, making space for breaking old patterns in therapy.

Therapy, then, is not about preventing collapse but about learning how to meet it. It teaches us to see the flood as part of life, the fire as a force that clears, and the shadow brother as a companion in disguise. Renewal becomes possible when we stop resisting the inevitability of endings and begin to engage the work of rebuilding. Every kingdom falls, but in that fall lies the possibility of a deeper, more resilient self.

If you find yourself in a season of collapse or transition, know that you do not have to navigate it alone. At Luceris Psychotherapy Clinic, we walk with clients through these moments of loss, change, and reorganization. Contact us today or begin the work of renewal and discover what can emerge on the other side.