Anxiety as the Cost of Foresight

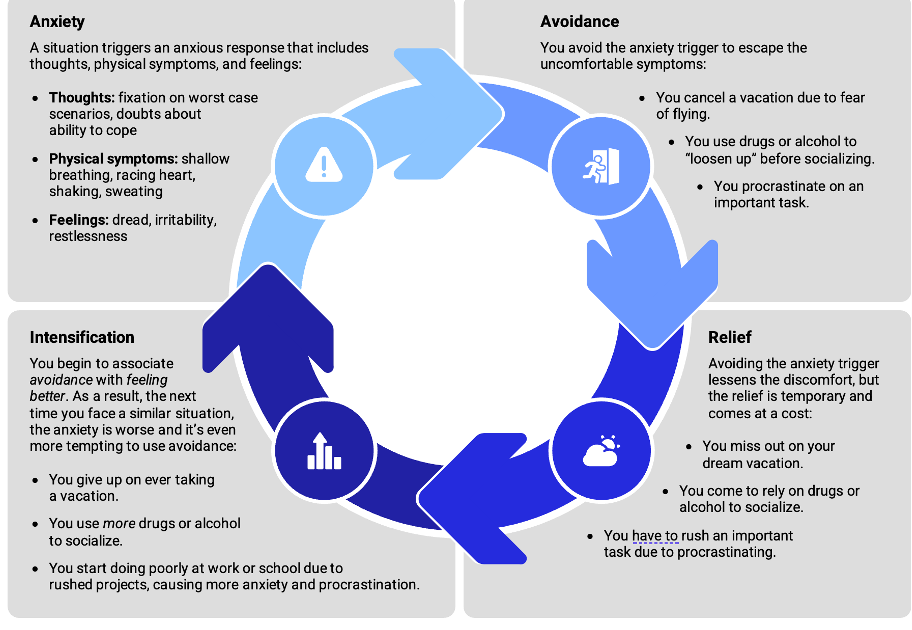

Picture this: you’re sitting in a quiet room. Nothing is happening. No threat is near. Yet your chest tightens, thoughts scatter, your body prepares for something you cannot name. That’s anxiety. It rarely waits for an obvious danger. It arrives because human beings carry something most animals do not, the ability to imagine what might come next. Rebuilding trust in therapy begins here, with learning how to face that constant anticipation without being ruled by it.

Evolution gave us foresight, and with it came a price. A zebra on the plains grazes calmly while lions sleep nearby. It does not pace and stew over what the lions might do tomorrow. But we do. We are capable of picturing not only one lion but the entire category of danger: all the things that could go wrong today, tomorrow, or years from now. That gift of abstraction has kept us alive. It has also left us vulnerable to endless unease.

Neuroscience traces this to the vigilance systems deep in the brain, the reticular activating system, the amygdala, and the circuits that keep us awake when threat seems possible. Anxiety doesn’t always signal a predator in the room. Often, it signals the category of predators in our imagination. Our body reacts to the “what if” as if it were happening right now. This is why the nervous system can be on high alert in a safe space. Consciousness itself is partly built on this constant watchfulness.

Constructivism gives another angle. Jean Piaget observed that children (as us adults) grow when they encounter something that doesn’t fit their current map of the world. He called this disequilibrium. Anxiety is the adult version of that moment. It’s the jolt when life no longer fits the model you’ve been using. A job loss, a medical test, an uneasy silence in a relationship, suddenly, the categories you relied on don’t seem to work. Anxiety is your body insisting that the old map is incomplete.

This is where therapy enters, not as reassurance that the world is safe, because it isn’t, but as guidance in building a more resilient map. Exposure therapy is one of the most direct ways to do this. It does not promise the removal of fear. Instead, it helps you encounter uncertainty in small, structured steps, long enough for your nervous system to learn something new: fear can rise without destroying you. You discover not that life has no danger, but that you are less fragile than you thought.

We expect exposure to feel like being shoved into the deep end. In truth, it is more like wading into cold water, inch by inch, until our body adjusts. A person who avoids elevators may begin by standing a few feet away from one. Their hearts race, palms sweat, yet nothing catastrophic happens. That is the new information their system needs. The next week, they step closer. Eventually, they ride for a single floor. Each small victory rewrites the map. The elevator stops being a tomb. It becomes what it actually is: a machine that carries people from one floor to another.

But beneath the surface, something deeper is happening. Exposure is not only about elevators or public speaking, or social fears. It is about the nervous system learning that the unknown itself is survivable. Therapy here functions like a modern initiation: guiding people into the dark places where their imagination spins its worst and helping them emerge with new strength. What once felt like chaos becomes part of an expanded world.

Anxiety will never disappear; it is too deeply wired into us. But it can shift roles. From an enemy that keeps you cornered, it can become a signal that you are brushing up against the edge of growth. Therapy doesn’t silence the alarm. It teaches you to walk forward anyway, map in hand, knowing you can redraw it as you go.

The same principle that underlies anxiety, the failure of the old map to cover new territory, also explains the rise of resentment, the collapse that follows betrayal, and the stagnation that comes from avoiding responsibility. Each of these moments signals disequilibrium, the demand for reconstruction. In the sections that follow, we’ll trace how rebuilding trust in therapy helps people face these crises, not by erasing them, but by turning them into the raw material for a more resilient and meaningful life.

Resentment and the Weight of Silence

Resentment often grows in the space where words should have been. A person avoids conflict for the sake of peace, believing that silence will keep the relationship intact. Another takes on more than they can manage, convinced that sacrifice will secure love or respect. For a time, these strategies seem to work. Yet the body notices the imbalance, and slowly a heaviness develops. Resentment is the name we give to that weight.

From a constructivist view, resentment signals disequilibrium. The framework that once kept life coherent no longer fits. Piaget explained that growth happens through two processes: assimilation, when we fold new experiences into an existing map, and accommodation, when we revise the map itself to make sense of something that doesn’t fit. Children adapt this way constantly; a puzzle that resists one strategy forces them to try another. Adults do the same, though the puzzles are more complex. When resentment appears, it often marks the place where assimilation and accommodation have stalled. Silence or sacrifice can no longer integrate new experiences, but change feels too risky to attempt.

Nietzsche warned that ressentiment (resentment) left unaddressed becomes dangerous. He described how people who cannot act on their grievances reframe the world instead. Strength in others is cast as arrogance, vitality as corruption. The longer resentment festers, the more it reshapes perception, until bitterness feels like truth itself. Contemporary psychology observes the same dynamic. Rumination deepens, relationships erode, and the self becomes defined by grievance. What began as an emotional protest turns into a distorted way of interpreting reality.

Therapy approaches resentment as a clue to where meaning has broken down. The task is to understand whether the signal points outward or inward. If it points outward, boundaries may have been crossed repeatedly without acknowledgment. Therapy provides the structure to practice naming these moments, often through assertiveness work that helps clients give shape to needs they had learned to suppress. The act of speaking, even in small ways, begins to repair the gap between experience and expression.

When resentment points inward, the problem lies in avoided responsibility. The individual has held back from action, whether out of fear, habit, or uncertainty, and the cost appears as bitterness. Here, therapy resembles exposure. Just as someone learns to face feared situations step by step, clients practice approaching the responsibilities they have avoided. Each attempt updates the internal model: action is possible, avoidance is not the only path.

Resentment is corrosive when ignored, but it can also serve as an inflection point. It shows where the map of life no longer aligns with the territory. Rebuilding trust in therapy helps people examine that mismatch, test new responses, and rebuild their frameworks in ways that restore both agency and clarity.

Betrayal and the Collapse of the Map

Few experiences dismantle a person’s sense of reality as thoroughly as betrayal. It is not only the act itself, the broken promise, the deception, the sudden fracture of trust, but the way it spreads backward and forward in time. People reinterpret what once felt stable through suspicion. They rewrite what might have been possible in the future as uncertainty. Betrayal collapses the scaffolding that made the world coherent.

Psychologists have studied this rupture as a form of assumptive world-shattering. Janoff-Bulman described how people hold deep beliefs that the world is predictable, relationships are trustworthy, and life has meaning. When betrayal strikes, these assumptions crack. The partner, friend, or colleague is no longer only the individual who acted; they become a symbol of instability itself. The mind begins to ask: if this was not what I thought it was, what else in my life is fragile? Constructivist theory frames this as the collapse of a schema. The old map, once functional, no longer explains the territory. Disequilibrium sets in.

Interpersonal attachment research shows why betrayal cuts so deeply. Secure bonds give us a foundation to explore and endure difficulty. When that bond becomes the source of danger, the nervous system enters chaos. The body alternates between protest, clinging for reassurance, and withdrawal, as if no strategy will bring safety. In therapy, the first work is often to steady the ground. Just as exposure therapy breaks down overwhelming fears into tolerable steps, betrayal recovery relies on titration, the practice of processing trauma in small, manageable doses so healing can happen without overload. Clients start with story fragments they can hold without collapsing and gradually build the capacity to face the full reality. Therapists guide them to notice how grief and anger rise in the body, and they pause before those emotions overwhelm. Over time, the nervous system learns to recall, feel, and understand the betrayal without falling apart.

Nevertheless, constructivism highlights that healing does not mean restoring the old map but building a new one. The betrayed person cannot return to the naive trust that once structured their world. Instead, they construct a revised framework, one that acknowledges human fallibility, integrates lessons about boundaries, and still leaves room for connection. This reconstruction is slow, often painful, but essential. Without it, bitterness ossifies, and new relationships are strangled by suspicion. With it, the person begins to carry both knowledge of vulnerability and the possibility of trust.

In a similar light, meaning-making is central here. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, observed that suffering becomes bearable when it is given meaning, even if the meaning emerges only after deep struggle. Rebuilding trust in therapy invites clients to articulate what the betrayal has taught them, not in the language of justification, but in terms of wisdom. Sometimes the lesson is about the limits of control, sometimes about the necessity of voice, sometimes about the recognition of their own resilience. This meaning does not erase the pain, but it transforms it into something livable, something that can guide the next chapter of life.

Betrayal, then, is not only a wound but an invitation to rebuild. Therapy does not offer shortcuts through it. It offers companionship, structure, and language so that the fragments can be gathered, and a new map of reality can emerge.

Avoided Responsibility and the Unlived Life

Resentment and betrayal reveal a gap between the world people imagined and the world they face. Another form of suffering emerges when someone continually avoids responsibility. Unlike sudden betrayal, this avoidance unfolds quietly. People delay tasks or leave difficult truths unsaid. Over months and years, these choices narrow life. What starts as self-protection eventually hardens into limitation.

Alfred Adler described this in terms of discouragement. Human beings, he argued, are driven by a deep urge toward significance and belonging. When early experiences leave someone feeling inferior, the fear of failing again can make responsibility feel unbearable. The child who was scolded for mistakes becomes the adult who avoids new challenges. The partner who grew up unseen learns to stay silent rather than risk confrontation. Adler believed that growth requires what he called social interest, the willingness to step into contribution despite the risk of inadequacy. Without it, avoidance becomes the governing strategy, and bitterness often follows.

Marie-Louise von Franz, explored this pattern in myths and fairy tales. She noted that characters who avoid their tasks, who refuse the call, or who trick their way out of responsibility rarely escape the consequences. The unlived life appears as a curse, a haunting presence, or a figure of decay. Von Franz observed that what is not faced does not vanish; it returns in distorted form. Clinically, this is clear in us who project hostility onto others for qualities we have refused to cultivate in ourselves. A person who avoids standing up for their needs may come to see every colleague as domineering. The shadow aspect of their personality, the suppressed or disapproved of aspects for the sake of survival and acceptance, is not a monster from within but the unlived parts of life left unclaimed.

Constructivism gives us another lens. Avoidance of responsibility halts assimilation and accommodation, the two processes Piaget described as central to growth. As seen above, assimilation is when a new experience is fitted into the existing map; a challenge at work might be absorbed as proof of competence. Accommodation is when the map itself changes to account for what cannot fit, realizing, for example, that asking for help is not a weakness but part of mastery. When responsibility is avoided, neither process takes place. New experiences are filtered out because they would demand change. The map becomes static, while the world continues to move. Eventually, the mismatch grows so wide that resentment or despair fills the space. Therapy aims to restart the process. Exposure is one method, not just for fear of elevators or crowded rooms, but for avoiding responsibility itself. A client may begin by naming a long-delayed truth in session, then practicing small steps toward ownership outside of it. Each act enlarges the self-schema: “I can act, and I can withstand the consequences.”

Avoiding responsibility is often more frightening than an overt threat, because it requires turning toward inadequacy. Adler saw this clearly: the fear of being “not enough” is one of the most paralyzing forces in human life. Yet he also believed that courage grows precisely at this point.Clients rebuild trust in therapy by practicing courage, naming the unlived life, and beginning the work of stepping into responsibility.

Reconstruction and the Work of Therapy: Rebuilding Trust in Therapy

This is where narrative reconstruction becomes central. Robert Neimeyer’s research shows that people heal when they can reorganize their story: what happened (sense-making), why it matters (benefit-finding, if any), and who they are now in light of it (identity reconstruction). Scaffolding, a generic term referring to a process used in multiple therapy models, involves the therapist helping to break down overwhelming material into parts the client can approach without becoming engulfed.

In practice, clients might revisit just one moment of the betrayal at a time or write a letter they never send, using it to give shape to their words. Each piece they approach safely gives the nervous system evidence that they can name chaos and survive it.

When betrayal shatters basic assumptions, that the world is safe, that people can be trusted, that life is coherent, the pieces do not simply fall back into place. Janoff-Bulman described how these assumptions collapse, but the harder question is what comes next. Left alone, people often cycle between suspicion and despair. In therapy, the task is to work with those fragments until a new framework can emerge.

Over time, the fragments begin to link together. What once felt like scattered, unbearable memories starts to form a narrative. A client may move from “I was blindsided and destroyed” to “I was betrayed, I grieved, and I am learning to rebuild trust on clearer terms.” This shift does not deny the pain; it integrates it into a larger story where the self is not only a victim of collapse but an active agent in reconstruction.

Without scaffolding, clients risk swinging between numbing avoidance and emotional flooding. With it, they practice tolerating pieces of the truth while maintaining stability. The process is deliberate: not rushing toward resolution but carefully widening capacity until new meaning can take hold.

The point is not to restore the world as it was, because it cannot be. It is to build a new framework that can hold complexity, trust alongside caution, vulnerability alongside resilience. In this sense, rebuilding trust in therapy does not erase shattered assumptions but uses them as the ground from which a more durable sense of self and world can be constructed.

Living With a Revised Map: Rebuilding Trust in Therapy

Across resentment, betrayal, and avoided responsibility, one theme has carried through: life breaks down when the old map no longer fits. Resentment signals the places where silence or sacrifice can no longer contain experience. Betrayal collapses assumptions about trust and meaning, leaving fragments that demand reassembly. Avoidance of responsibility narrows life until what is unlived returns as bitterness. Each is painful in its own way, yet each also opens the door to reconstruction.

Rebuilding trust in therapy works by turning these fractures into material for growth. Constructivism shows that we are always revising the frameworks we live by. Narrative research shows that healing begins when people weave their suffering into a story they can carry. Clinicians use scaffolding, exposure, boundary-setting, grounding, and dialogue to help clients face what feels unbearable without becoming overwhelmed. Bit by bit, the nervous system learns to face fear, tolerate grief, and take up responsibility. What once narrowed life begins to enlarge it.

The point is not that resentment vanishes, betrayal is forgotten, or responsibility becomes easy. The point is that with a revised map, these realities no longer define the whole terrain. They become part of a broader framework, one that holds both suffering and possibility. The question for each of us is not whether difficulty will come; it will, but what we will make of it when it does. Will we retreat into silence and avoidance, or will we take the fragments and begin to rebuild?

If something in this reflection resonates with your own life, consider booking an appointment with Luceris. You can also contact us directly with any questions or inquiries.