In a group of chimpanzees, tension can spread quickly. One animal stiffens, another bares its teeth, and the whole troop feels the shift. Their bodies speak an old language of emotion, one that helps them survive. We carry that same language inside us. Research shows that deep in the brain are systems for fear, grief, anger, care, and play that have been with mammals for millions of years. Therapy for overwhelming emotions begins by showing people that these feelings are not flaws. They are ancient survival responses, and with guidance, clients learn to understand them and work with them in the present.

When people come to therapy, they often feel ashamed of these emotions. Panic feels like weakness. Grief feels like failure to “move on.” Anger feels dangerous. Yet these feelings are not accidents. They are ancient survival responses. Anxiety is tied to the vigilance that once helped our ancestors spot predators. Sadness draws from the same bonds that kept infants close to parents. Even anger has its roots in protection and self-respect.

The trouble is that these systems can sometimes flood us. A nervous system built for life in the wild struggles to keep balance in the modern world. That is where therapy begins. Instead of trying to erase emotions, therapy helps people approach them with new understanding. In sessions, clients learn to notice fear as it rises, stay with it long enough for the body to steady, and discover that what once felt unbearable can, in fact, be endured. With time, emotions that once appeared as enemies begin to act as guides.

Stories help us see this more clearly. Across psychology, myth, and neuroscience, the same truth emerges: emotions are not defects to erase but survival codes written deep into us. From the politics of chimpanzees to the symbols of dragons and underworlds, and finally to the quiet work of therapy, we’ll see how learning to face what overwhelms us is how people reclaim balance, strength, and meaning.

Therapy for Overwhelming Emotions: Fear and the Unknown

Chimpanzees live in groups where danger is never far away. A rustle in the grass could mean a predator. A challenge in the hierarchy could bring a fight. Neuroscience shows that their fear circuits, buried deep in the limbic brain, look a lot like ours. Jaak Panksepp mapped these as the FEAR system; a network that lights up when survival feels threatened. We inherit the same system. Our bodies still react as if the world is filled with predators, even if today’s threats are deadlines, social judgment, or the unknown future.

Fear is not just an emotion; it is an ancient signal for survival. The amygdala fires, stress hormones surge, muscles tense. The body prepares to run, fight, or freeze. This system kept our ancestors alive, but in modern life it often misfires. A presentation at work, walking into a crowded room, or speaking honestly in a relationship can all ignite fear as if life itself were at stake.

Myth captures this experience in vivid images. Think of the dragon guarding treasure, or the hero standing at the edge of a dark forest. Or Shrek saving Fiona the princess from the castle guarded by a dragon! These creatures represent fear itself, the sense that something dangerous and overwhelming lies ahead. The stories remind us that fear is not a sign of weakness. It is the natural response to stepping beyond what is known. To grow, the hero does not slay fear outright but learns to face it, step by step, until what seemed impossible becomes part of their strength.

Therapy for overwhelming emotions is a process is carefully supported. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) offers a practical way to work with fear. Instead of urging someone to “just be brave,” CBT breaks the fear cycle into smaller pieces. A therapist might help a client notice the thoughts that accompany fear, “I’ll fail,” “Everyone will laugh at me,” and how those thoughts fuel the body’s alarm. Then, through gradual exposure, clients test what happens when they enter feared situations in manageable steps. For example, someone afraid of speaking up might first practice with a trusted friend, then in a small meeting, and eventually in larger settings. Each step teaches the nervous system something crucial: fear can rise, but it does not have to decide the outcome.

This work is not about rushing headlong into terror. It is about widening the space between fear and action. Clients often find that what once seemed like a solid wall is in fact a threshold, intimidating, yet passable with support. The dragon of myth does not fall in a single strike. Heroes return to it again and again, watching, engaging, and wearing down its power until it changes form. Therapy for overwhelming emotions takes the same approach. Clients confront fear in small, supported steps, learning to read it not as an enemy but as a signal they can understand and work with.

Anger, Power, and Therapy for Overwhelming Emotions

Anger has always carried a double edge. On one side, it protects us. On the other, it can wound, isolate, or destroy. Neuroscience places this in what Jaak Panksepp called the RAGE system, a circuit that fires when boundaries are crossed, resources are threatened, or survival feels at stake. The body readies itself to fight: muscles tense, the heart pounds, and focus narrows. For our ancestors, this meant defending territory or kin. For us, the same system lights up in a meeting at work, during conflict at home, or even in traffic.

Chimpanzees show how primal and social this energy really is. Frans de Waal observed that aggression in chimp troops is rarely random. Displays of anger, hooting, charging, rising hair, often erupt when dominance is challenged. Yet the strongest leaders are not those who intimidate endlessly. The most successful alphas learn to use their power selectively, protecting allies and reconciling after conflict. Those who rule by fear alone eventually lose the support of the group. What de Waal uncovered in apes echoes in human life: anger without wisdom destabilizes everything around it.

Myth tells this story in another language. The tyrant king, consumed by resentment and cruelty, represents rage ungoverned. The wise king, who tempers strength with care, represents anger transformed into authority and protection. These archetypes live in all of us. Suppressed anger can turn inward, leading to depression or self-contempt. Unchecked anger bursts outward, leaving wreckage in its path. But integrated anger, acknowledged, expressed clearly, and contained, becomes a source of respect, both for oneself and from others.

Therapy for overwhelming emotions, like anger, is often the most avoided emotion. Many clients fear it, having grown up in homes where rage was destructive. Others bury it, convinced that expressing anger will cost them relationships. Yet unspoken anger often leaks out in resentment, sarcasm, or withdrawal. Therapy treats anger as information, not a defect. It signals that a need, value, or boundary has been crossed.

Assertiveness training gives this signal a voice. Clients learn to stand between silence and fury, naming anger as a boundary: “I felt dismissed in that conversation, and I want to be heard.” This differs profoundly from shutting down or shouting. The practice is deliberate and slow, involving role plays, attention to body cues, and reflection on personal history. Over time, clients discover that anger can protect dignity rather than destroy it.

Anger, then, becomes less a problem to erase than a force to shape. Just as a chimpanzee leader tempers dominance with protection, or a mythical king transforms raw power into justice, therapy guides people to reclaim anger as part of their humanity. It is the shift from being ruled by rage to learning to rule with it.

The Shadow and the Monster Within

Every society has imagined monsters. They appear as dragons, demons, giants, or tricksters. What makes them compelling is not that they are foreign but that they feel strangely familiar. Carl Jung argued that such images represent the shadow, the parts of ourselves we push out of awareness because they feel unacceptable. This shadow includes cruelty, envy, and rage, but also ambition, pride, or sexuality. Suppressing them does not erase them. It simply drives them underground, where they shape our lives invisibly.

Evolutionary psychology helps explain why these impulses exist in the first place. Our ancestors lived in groups where cooperation mattered, but so did competition. Traits like aggression, dominance, or envy gave individuals leverage in resource struggles. Chimpanzees show us this in action. Frans de Waal observed that even the most stable leaders relied at times on aggression, but they also reconciled and protected. Aggression alone destabilized the troop. It was aggression paired with alliance and care that preserved social order. These drives are not mistakes. They are part of the equipment that allowed groups to survive.

The tension comes when cultural or personal morality declares these impulses unworthy. Nietzsche warned that certain moral systems demand the denial of natural instincts in the name of “virtue.” The result is not harmony but resentment. Suppressed anger turns inward, corroding self-respect, or erupts outward in distorted forms. A person who believes ambition is selfish may bury it, only to feel bitterness at others’ success. Someone convinced that anger is sinful may repress it until it breaks through in destructive outbursts. Morality that leaves no room for instinct becomes a breeding ground for shadow.

Myth reflects this danger. Heroes who refuse to face the monster are eventually consumed by it. Yet myths also carry another truth: integration is possible. By turning toward the frightening figure, whether dragon, demon, or underworld god, the hero gains something essential. The monster’s strength becomes part of their own. Jung described this as “growing teeth.” A person who recognizes their own capacity for harm paradoxically becomes less dangerous, because they can choose responsibility rather than act unconsciously.

Therapy for overwhelming emotions becomes the arena where this work comes to life. Within cognitive-behavioral approaches, the process may involve examining automatic thoughts that disguise envy, pride, or hostility. Schema therapy might reveal how a “self-sacrificing” pattern hides unspoken needs for rest or recognition. Psychodynamic work often traces projections back to their roots, showing how the selfishness condemned in others reflects what is disowned in oneself. Though the techniques differ, the underlying task remains the same: bringing the hidden into awareness.

The goal is not to glorify aggression or envy, but to acknowledge their place in being human. Anger, when integrated, becomes assertiveness. Ambition, when accepted, becomes the pursuit of growth rather than domination. To face the shadow is to take what is frightening within and make it part of one’s strength. Like the hero returning from the underworld, therapy helps people reclaim the very qualities they once feared, transforming them into resilience, dignity, and depth.

Life always moves between what is familiar and what is uncertain. Jung described this in mythic terms as the balance of order and chaos. Too much order, and life becomes rigid, oppressive, or stagnant. Too much chaos, and it unravels into fear, confusion, or despair. Human beings are wired to seek both stability and exploration, and psychology gives us frameworks to understand this tension.

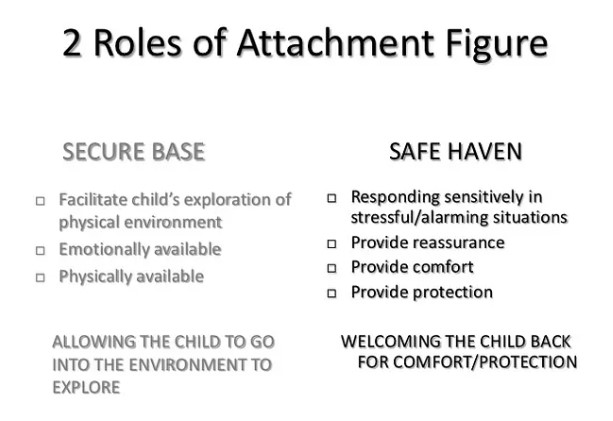

Attachment theory shows it early in life. A securely attached child uses the caregiver as a “secure base,” venturing out to explore but returning for comfort when needed. The balance between safety and risk becomes the foundation for resilience. When this balance is disrupted, through neglect, inconsistency, or intrusion, children may cling to order anxiously, or avoid closeness altogether, shrinking back from exploration. Adults carry the echoes of this in their relationships and in their tolerance for uncertainty.

Cognitive psychology highlights the same pattern. Jean Piaget observed that development unfolds when children encounter situations that do not fit their current understanding, what he called disequilibrium. If the challenge is too overwhelming, they collapse into confusion. If it is too easy, nothing changes. Growth happens in the zone where stability meets disruption, allowing old schemas to adapt into new ones. This principle shows up directly in therapy. Clients grow not by clinging to what feels safe, and not by plunging into what floods them, but by pushing at the very edge of what they can hold.

Evolutionary psychology explains why this matters. Our ancestors who clung too tightly to the familiar risked missing new resources or failing to adapt to changing environments. Those who sought novelty without caution risked injury or death. Survival favored those who could balance exploration with stability. Neuroscience reflects this as well. The left hemisphere tends toward categorization and order, the right hemisphere toward novelty and vigilance. Meaning arises when both work together.

Myth translates this into images we intuitively understand. In The Lion King, Mufasa tells Simba that everything the light touches is his kingdom, the known, the ordered. Beyond lies the elephant graveyard, the unknown and dangerous. To live only in the light is to stagnate. To wander into darkness without guidance is to be consumed. Growth requires venturing into the unknown with enough grounding to return changed.

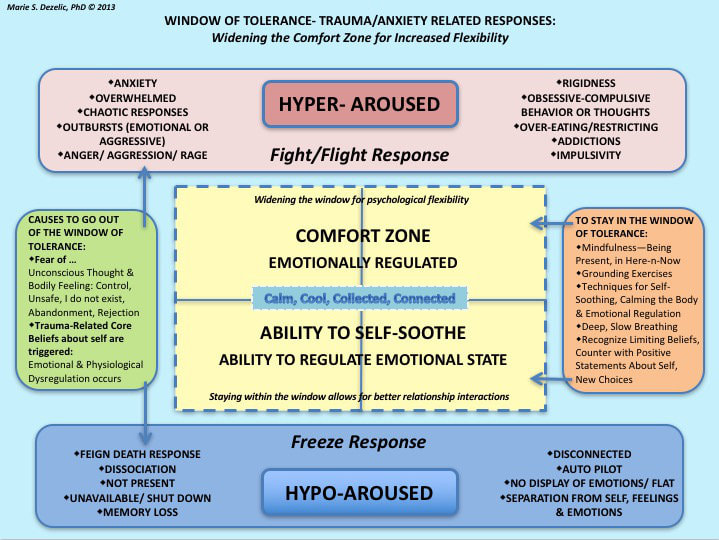

Therapy for overwhelming emotions often sits at this threshold. A client who avoids all conflict clings to order, but their relationships become brittle. Another who is consumed by trauma may feel pulled into chaos, unable to find ground. Therapy helps expand what trauma theorist Dan Siegel calls the “window of tolerance.” Within this window, emotions can be felt and processed without overwhelming the nervous system. Over time, the client learns they can step toward uncertainty, grief, or fear without collapsing into chaos, and also that structure and safety need not harden into rigidity.

To live is to walk the line between what we know and what we do not. Chimps show us this in their hierarchies, balancing aggression with reconciliation. Myths remind us of it through dragons at the edge of the forest. Psychology confirms it in theories of attachment, development, and trauma. And therapy gives it form in practice, helping people hold both order and chaos, safety and risk, until they find a life spacious enough to grow.

Closing Reflection

What makes therapy for overwhelming emotions powerful is not that it erases emotions but that it changes how we live with them. Fear, anger, and longing are not new inventions. They are ancient systems we share with other primates, embedded in the brain long before reason took shape. Myth gave us dragons, tyrants, and underworlds to capture what it feels like when those forces rise. Psychology has mapped how they emerge, how they overwhelm, and how they can be transformed.

Fear showed us the edge of the unknown. It surges when life asks us to step forward, whether into a classroom, a relationship, or an uncertain future. Therapy gives that fear a place to be understood. Anger revealed itself as more than danger, it is the voice of boundaries, capable of becoming protection when guided with care. Therapy turns raw rage into assertiveness, helping people move from silence or explosion into dignity. The shadow reminded us that what we disown never disappears. Therapy offers the courage to meet those hidden parts, reclaim their strength, and integrate them into a fuller sense of self.

At every step, the tension between order and chaos remains. Too much order, and life hardens into rigidity. Too much chaos, and it dissolves into confusion. Therapy for overwhelming emotions is where people learn to walk that line, to feel enough safety to stay grounded, enough openness to grow.

None of this is abstract. Clients live it each time they face the fear they thought would crush them, express the anger they once buried, or allow grief to take its place without drowning them. These are not small adjustments. They are transformations. They are the modern form of the ancient stories: the descent, the confrontation, the return.

In that sense, therapy for overwhelming emotions is less about solving problems than about reshaping the story a person lives in. The monsters, tyrants, and shadows do not vanish, but they lose their power to dominate. What once felt unbearable becomes part of a larger pattern of meaning. To enter therapy is to accept the invitation to change, not by discarding what is human, but by learning to carry it with greater strength, depth, and clarity.

Book an appointment with Luceris if you found something in this article you wish to reflect on in therapy or shoot us a message if you have a question or seek clarity.